The European Banking System Is Flat-lining

- Chris Skinner , Chairman at Financial Services Club

- 20.03.2017 12:30 pm European Banking , Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, the Finanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal’s Financial News.

There was an interesting article in The Independent last week about the big banks becoming bigger since the financial crisis hit. The article notes that the big American banks control 70% of all US assets, and that this figure has increased 40% since 2008.

In the lead up to 2008, parallel to increasing debt levels, the size of banks rose sharply, especially relative to the size of certain economies. By 2007, bank assets in many developed countries had reached in excess of 100 per cent of gross domestic product (“GDP”).

In 2007, bank assets in the US were around 78 per cent of GDP. In Japan it was around 160 per cent. In Germany, it was around 270 per cent. In Italy and Spain, it was 213 per cent and 269 per cent respectively. Ireland’s bank assets were over 700 per cent of GDP. Iceland’s bank assets were nearly 900 per cent of GDP. Bank assets to GDO was over 500 per cent in the UK and over 600 per cent in Switzerland, reflecting in part the role of these nations as major financial centres channelling capital flows between third countries.

The banks feed domestic credit, financing asset purchases, investment and consumption as well as cross border lending. As banking became more international, cross border capital flows peaked in 2007 at around US$ 12 trillion, a rise from US$500 billion in 1980 reflecting an annual increase of around 12 per cent.

In the US, at its peak, the finance industry generated 40 per cent of corporate profits and represented 30 per cent of the market value of stocks. In the US, since the crisis, the six largest US banks now control nearly 70 per cent of all the assets in the US financial system, having increased around 40 per cent (against overall asset growth of only 8 per cent). JP Morgan, the largest US bank, has over $2.4 trillion in assets, larger than most countries.

A large banking system is not necessarily problematic. For example, in the UK, reflecting the status of London as a major global financial centre, financial services contribute significantly to economic activity. Financial and insurance services contributed £125.4 billion in gross value added (GVA) to the UK economy or 9.4 per cent of the UK’s total GVA, around 46 per cent from London alone. Trade in financial services contributes significantly to the UK’s trade surplus in services. The sector’s provides 3.6 per cent of UK jobs is around 3.6 per cent and contributed £21.0 billion to UK tax receipts in 2010-11.

But a large banking system creates a number of issues.

Those issues include banks becoming too central to the running of the economy; when the domestic economy becomes too flat, banks use leverage to increase profits; the need for shareholder returns then creates increased risk taking; that risk taking leads to the launch of new financial innovations that are untested and unproven; this leads to too much complexity in the markets and cross-border movements of capital; ultimately it leads to failure, but the banks know that they won’t fail as governments will underwrite them as lenders of last resort.

It’s a kind of vicious rather than virtuous circle: banks take risks which, if they fail, force their government to bail them out.

In the US and globally, the combination of too big to fail plus a relaxation in measures designed to modest reduce financial sector make be laying the foundation for another financial crisis.

I read this article at the same time as I picked up Handelsblatt’s quarterly magazine. Unavailable online, it had a fascinating article about Europe’s banks featuring content I’d not seen elsewhere. Sure, we know that some of Europe is a basket case – Greece, Cyprus – but Germany? German banks seriously in trouble? OK, I heard the IMF calling Deutsche Bank systemically dangerous but they’re not going to fail, are they?

Well, this article explained the issue well, so here goes.

Few follow the continued wreckage to the shipping industry with greater alarm than Germany’s banks. A massive lending binge to shipping companies in the years leading up to the financial crises has left some leading banks dangerously exposed. Despite a decade’s worth of debt write-offs and bailouts, German banks still hold some €90 billion in shipping loans – around a quarter of the global total – with disastrous consequences as the debts continue to sour. Last month, the country’s largest lender, Deutsche Bank, warned that losses on its shipping portfolio could hit €34 million this year, three times the 2016 figure. Rival Commerzbank says it will be setting aside up to €600 million to cover possible maritime losses …

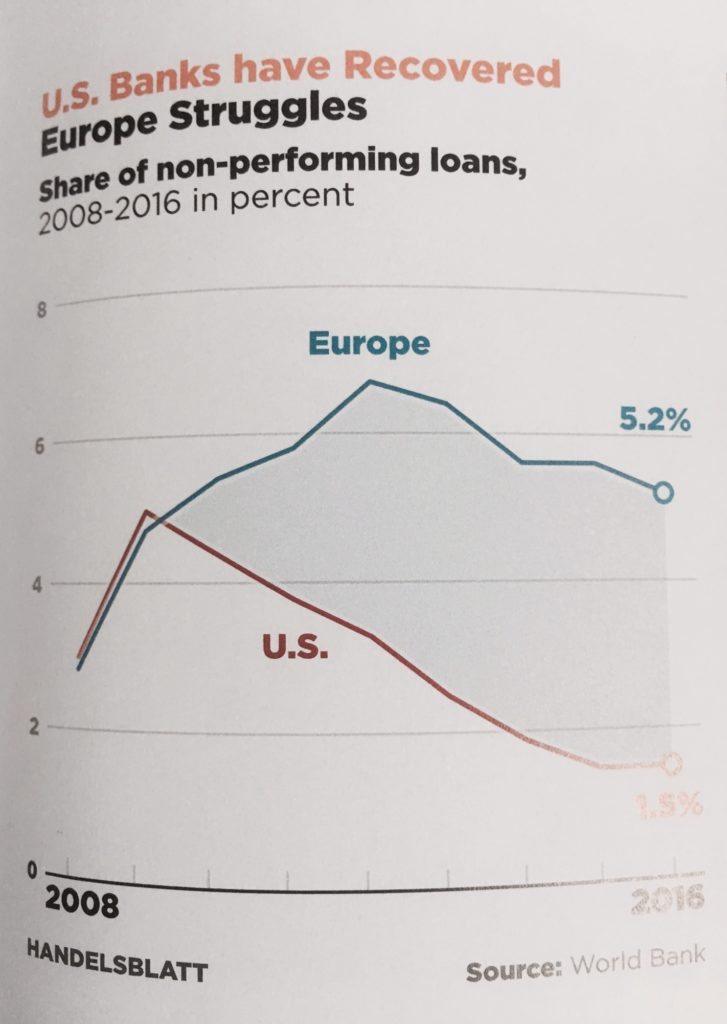

Consider the facts. A 2016 KPMG report revealed that one decade after the financial crisis, Europe’s banks still carry non-performing loans – where the borrower is paying no interest and repaying no capital – worth €1 trillion, almost three times the figure in the United States. In Italy, where the much-publicised woes of the world’s oldest banks, Monte dei Paschi, have threatened to bring down the entire banking systems, a full 15 percent of loans are now deemed non-performing. But that share is trivial compared to the plight of banks in Greece and Cyprus, where the figure tops 40 percent …

To be sure, the picture if far from uniform. In the Nordic countries, many banks have more or less managed to clear their books of bad debts through sales or write-downs, while in Germany, non-performing loans make up just 3.5 percent of the total (see chart). But there is little room for complacency …

The problem is writ large across much of Europe. While the Eurozone and the US both started with similar shares of bad debt during the financial crisis, the share has come down in America but stayed high in Europe (see chart). One reason seems to be that US regulators were tougher in forcing debt write-offs, recapitalisations and even bankruptcies. For the American financial sector, the crisis is effectively over.

Hmmmm … thank goodness for Brexit, I guess.

The article was originally published on thefinanser.com: https://thefinanser.com/2017/03/european-banking-system-flat-lining.html/